Memoirs of a Gaijin

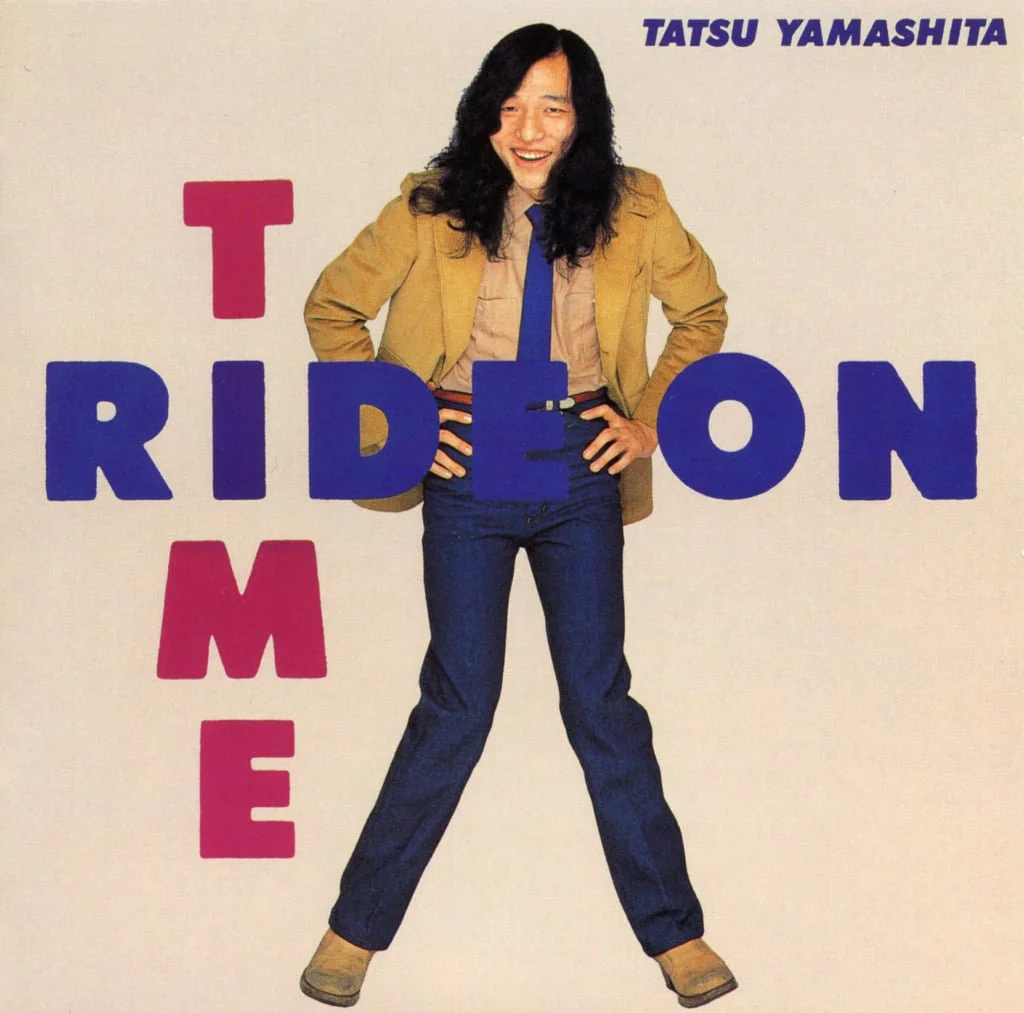

For the past 5 years I spent much of my life trying very hard to promote Japanese City Pop music, often neglecting all other facets of my life. I wanted so much to help spread this music that had been left in a state of neglect when I found it. I found a purpose in playing the music and making mixes to spread awareness of these Japanese artists who deserved a bigger audience than they had. Discovering Japanese artists brought a sense of meaning to my life after years of floating around in the Vaporwave scene searching for a deeper understanding of the world we live in. I found all of that and more while simultaneously developing a community around this genre that was still relatively unknown by the average music fan. Starting in 2016 after being inspired by hearing enough of it circulating in the Future Funk scene’s remixes, I decided to create the first mix of what I understood as City Pop which carried a certain audio aesthetic and western sound. I tried to find a mix of music in a similar style, but there had been none available anywhere. While there were many references to the music itself no one had actually put the time in to tie the original versions of these songs into a mix with similar-sounding Japanese oldies. It felt like the frontier of an old genre finding new life, and I was glad to help reintroduce it to the world via YouTube. The first-ever city pop mix (below) combined the most iconic of City Pop artists in a way that felt new and fresh for many people hearing it for the first time, because it was the first time they were played together in such a format.

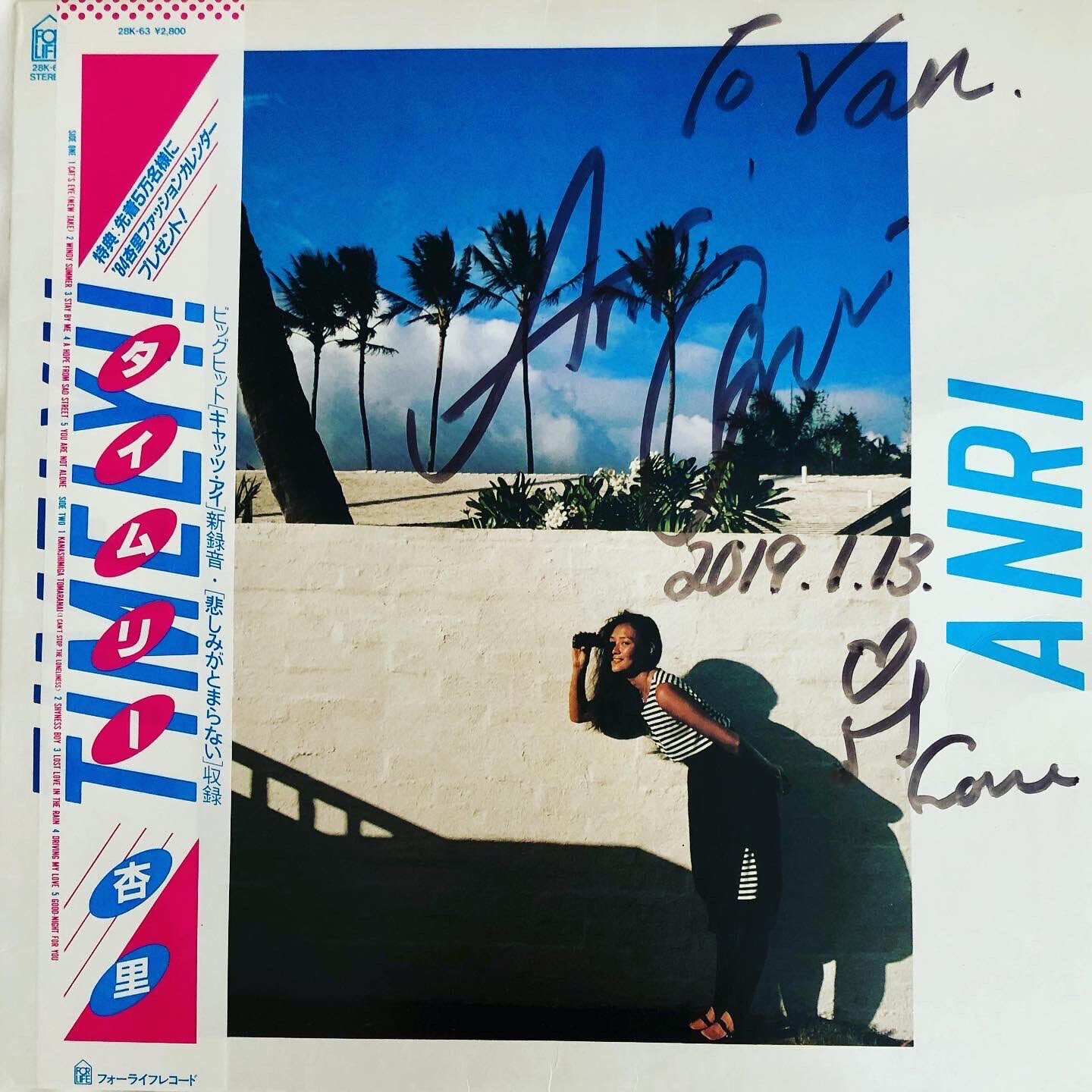

After many struggles with copyright issues, my channel had been copyright struck into oblivion by RIAJ (Recording Association of Japan). This was shortly past meeting Anri after helping to organize her first show in Chicago. I had met a friend of hers, an older DJ who owned a club in Tokyo, while DJing at a sake lounge in downtown Chicago and after I convinced him that her music was popular in the west he arranged for her to get a gig for the Japanese New Year in Illinois. I met her brother, who was also her manager after the show took place. I had been warned that he was a stickler about her music and was a tough character. While backstage I was presented to Anri where she signed my copy of her record, Timely, and after meeting with her I spoke briefly to her manager brother who presented me with his business card. I accepted the business card in the traditional Japanese manner, with both hands, so as to not seem culturally inept in front of this group of very important Japanese people. My nervousness however got to me and I accidentally dropped the business card. The air seeped out of the room like a window on a spaceship cracked open. My face was pale and I shuffled to pick it up, but I feared for the worst; that I had somehow disrespected Anri and her family forever tainting our relationship. I thought to myself that maybe it would be overlooked as a simple gaijin being clumsy and careless. Surely I would not be punished for such an innocent accident…

Shortly after this time, on February 14, 2019, my channel was gone. The length of time between meeting Anri, and the RIAJ taking down my channel was too uncanny. I knew I had messed up big time. During the conversation with her brother, I tried my best to convey that I wanted to help them do more with Anri’s music and was willing to do anything in my power to assist with the revival of her music in the west, but it was not enough. I had lost years of my effort and 100k subscribers in a matter of minutes. Appealing such decisions is a lost cause. For more hammering of the nail the majority of the music on my mixes had been licensed to YouTube shortly after anyway. I had a Japanese friend compose a very professional letter to RIAJ, and they responded that a personal complaint which was irreversible was the cause the hostile action. Even after committing to being an advocate for the music and not monetizing videos, I was left with nothing except fading relevance in a scene that I helped raise. At the time I had already acquired a huge amount of City Pop vinyl from Japan that was sold to me for practically nothing. It seemed that I was one of the first to start buying these records because they were in mint condition usually and for less than a thousand yen in most cases. No one had seen any value in them it seems, but I did. They held very special meaning to me, and I was always shocked that they were in such plentiful supply and Japanese record shops were willing to negotiate prices even further sometimes. I think they did find it odd that this westerner wanted these Japanese records though. My obsession with vinyl began with collecting City Pop records that became parts of me.

Hisashiburi CityPop Documentary (2018)

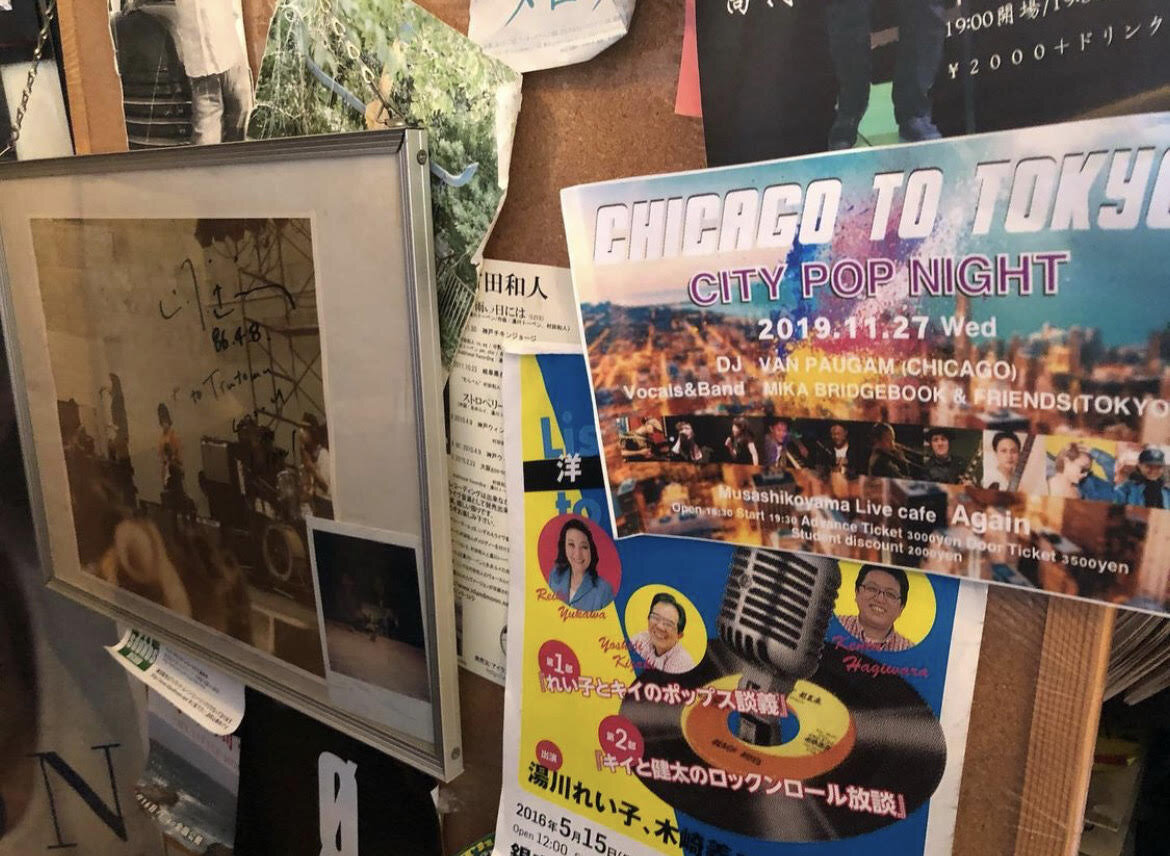

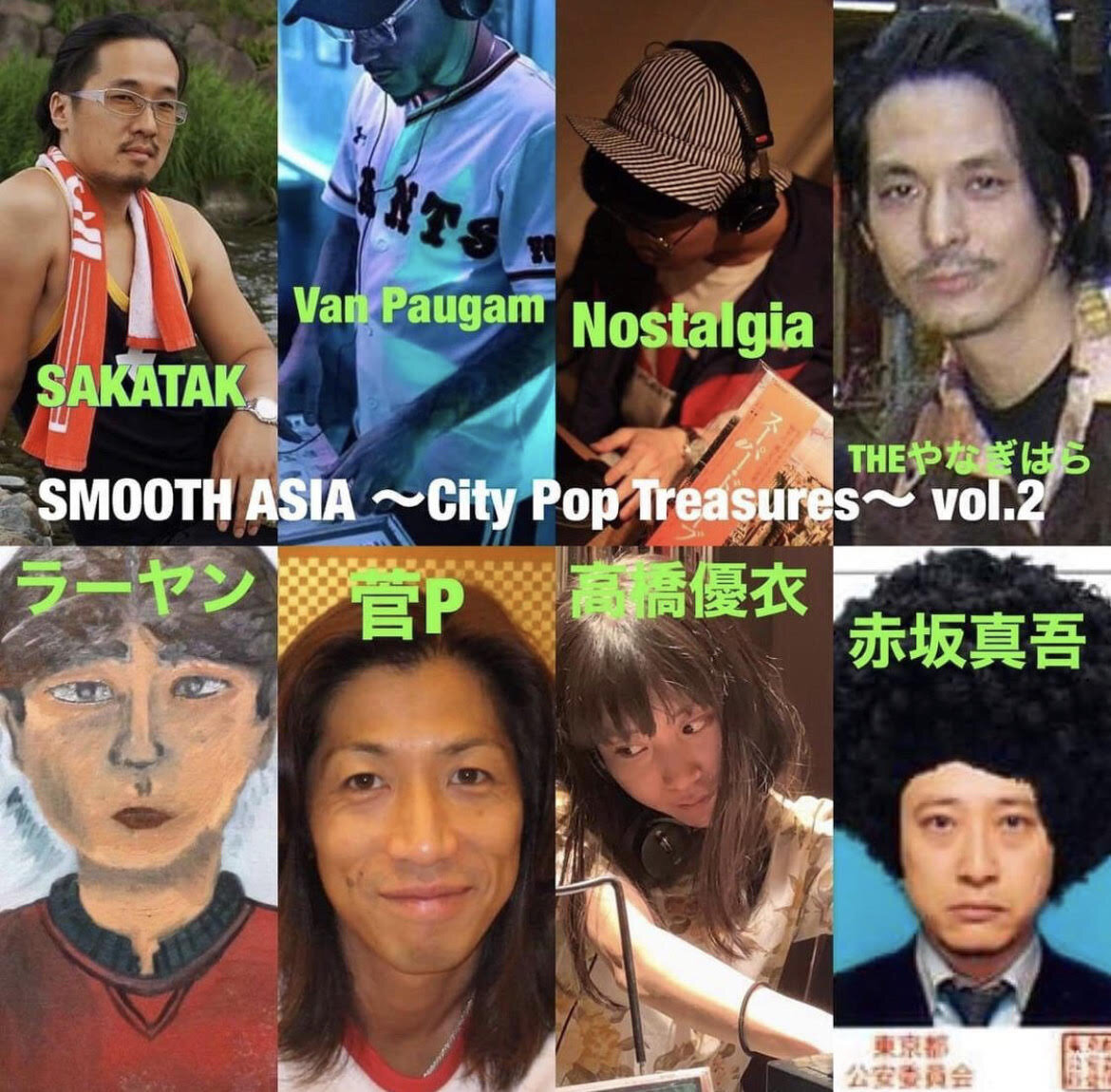

2019 would be a year of extremes for me because even though my channel had been eliminated, I still had 3 monthly DJ nights around Chicago dedicated to City Pop on vinyl including the only sake bar in the city, Murasaki Sake Lounge. Being the first person in Chicago to introduce the genre to the city earned me an interview with the Japanese Consulate, a feature in the local newspaper, and a part in a short documentary about the genre among other things. All this led up to being invited to play at multiple venues in Japan in what would be my first Tokyo tour in November of 2019. After meeting a Japanese singer named Mika Bridgebook during the filming of Hishashiburi CityPop in 2018 we became fast friends and planned right away to do a night in Tokyo. During my tour in Japan I was able to play at an iconic venue named Live Cafe Again next to the Legendary Pet Sounds record shop in Shinagawa, where Eiichi Ohtaki, the pioneer of City Pop regularly played. I was in the very spot where he frequented and sang some of the first proto-City Pop songs. I felt like I had come full circle to the roots of something that was far greater than myself. I had experienced a piece of history that not many would ever be able to do themselves. My channel being erased felt like a distant memory while there, and I finally felt a sense of peace from everything that had transpired that year. It was something I would never be able to forget, and memories that would shine brightly in a time that came just months before the pandemic changed the world forever.

Coming back from Japan I had realized so many things about my own life and the connection I had to City Pop. Even though I had been written out of the story by big media like Rollingstone, Vice, and Pitchfork’s articles on how the genre came to be popular again, I felt vindicated in what I had accomplished. Back in a time when not many had thought to even try DJ this kind of music I was excited to give it a shot not knowing how anyone would react to this kind of DJing. Little did I know the music would take me on a trip around the world from New York to Paris to Tokyo and more all while lugging around a crate of vinyl records through airports and busy streets just to play this music to people that came to know it through my mixes. I spent years of my life wanting to do something that was bigger than what I thought I could do, and I felt like I had done it. However, my identity that had been defined by this music for so long was unsustainable. I would never be accepted by the Japanese as a valid authority on the genre, and in the west, I was seen as appropriating the style which led to me being overlooked by popular media. Being left out of the history of how the genre came to the west was a final blow to my motivation to continue. I didn’t want to seem like I was disrespecting Japanese culture, and I didn’t want to continue looking foolish for trying to champion Japanese music when all roads were leading to my memory in the scene being erased.

So where does all this leave me? I feel like my goal was to help get City Pop more well known, and I think I accomplished that. As a Non-Japanese playing only Japanese music, it can appear problematic in the western world. We live in times that are extremely politically correct, but I have tried my best to be respectful of the music. Even though I still hold the music very dearly I think it is wrong for me to continue basing my entire identity around it. I want to approach Japan, and Japanese music from an even more respectful avenue by only writing about it and helping others understand its history more clearly. I will not be creating any new mixes unless sanctioned by the record labels or in collaboration with rights holders. I will still DJ live, as I have over 200 vinyl, but I will reduce my presence within the City Pop community, as it has already been diminished significantly since my channel went down anyway. I thank everyone who has supported me and given me credit for my work in resurrecting the genre. If and when I do DJ live it will be in part to support the AAPI community and help send a message of unity between Asia and the west. Thank you!

-Van

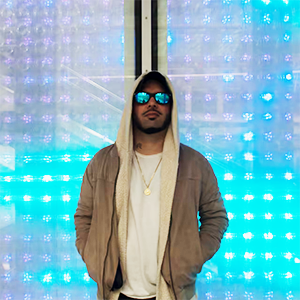

AUTHOR

Van Paugam is an Internationally-Acclaimed DJ and leading figure specializing in 70s and 80s Japanese Music, dubbed City Pop. He has organized and hosted over 100 events dedicated to the style, and actively promotes Japanese culture while on the board of the Japanese Arts Foundation of Chicago. He has been featured on CNN, NHK, and many other publications for his dedication to City Pop. Van is credited with being the first person to begin popularizing City Pop online through his mixes on YouTube in 2016, and subsequently through live events. Learn More…