Why is City Pop Nostalgic?

DISCLAIMER: The statements expressed below are my own, and not meant to be taken as anything other than opinions based on my personal experiences, thoughts, and conclusions about the topics discussed.

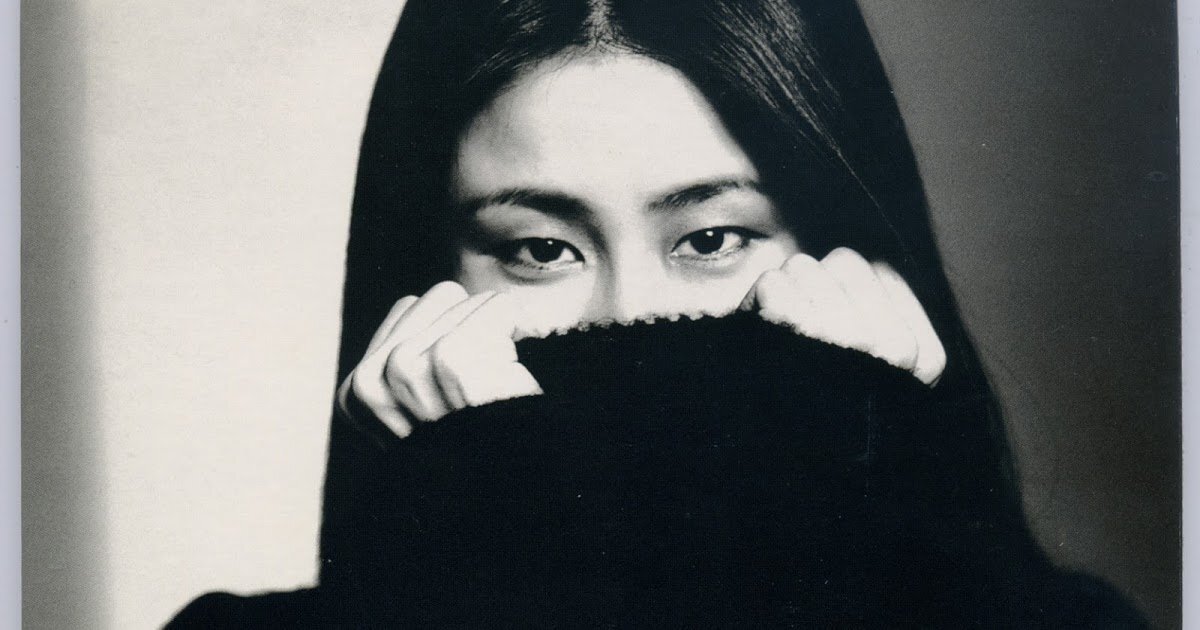

Momoko Kikuchi’s Album Cover for Ocean Side

Why is City Pop Nostalgic?

City Pop is a nostalgic genre of music for many people in the West for several reasons. Firstly, City Pop was popular in Japan during the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, a time when Japan was experiencing a period of rapid economic growth and cultural expansion. This era is often referred to as the "Bubble Economy" in Japan and is remembered as a time of great optimism and prosperity.

Secondly, City Pop is heavily influenced by Western music genres such as funk, soul, jazz, and rock, making it familiar and accessible to audiences in the West, especially for anyone who grew up listening to these genres. This fusion of Japanese and Western musical styles creates a unique and memorable sound that appeals to people across different cultures.

The economic powerhouse Japan maintained at the time is only starting to be charted in the west, but its neon-filled optimism has already captured the hearts and imagination of millions who think of it as nostalgic, but is it wrong to think of it as such?

Some argue that imprinting western ideals on Asian music for our satisfaction and comfort is wrong regardless if the music feels “nostalgic” or not. The topic of nostalgia is rarely explored in an international context and this specific phenomenon of eastern music resonating deeply in the psyche of western listeners is at a new frontier in our understanding of memory, music, and cultural exchange.

In order to understand why people describe City Pop as nostalgic you first have to understand what nostalgia even means. The Merriam-Webster definition of nostalgia reads: “a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for a return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition”. The curious part of the wording is that there no mention that this sentimental yearning needs to be tied to actual memories or places you’ve experienced yourself. My interpretation is that anyone can feel a legitimate longing for a past period even if not one they personally experienced, and they can desire for an irrecoverable condition even if belonging to a different culture.

This increasing consumption of City Pop by people overseas is partly due to the death of nostalgia in the west. Corporate blood-lust for older music that can sell a product to targeted demographic consumers has been a trend in a vast amount of television commercials, movies, and any manner of marketing that can take advantage of a specific longing for another time or condition. Older generations are having to deal with the music they once loved now being used to sell them tissue paper or car insurance while simultaneously sucking the life out their memories of the past.

In this case music from the 70s and 80s has been completely drained of all nostalgia and sentimentality due to being endlessly remixed, rebooted, and used for endless advertisements that parade the past as a selling mechanism to trigger trust and fond memories.

Nostalgia in the west has become just a way to sell something, and newer generations who have no real attachments to older music are looking for something to fill the nostalgic void in their lives. In this case, City Pop becomes the proxy to their own musical heritage by allowing them to create new memories free from the tainted grip of corporate interests or their parent’s upbringing.

Toshiki Kadomatsu

People in the west have grown with Japanese culture interwoven into almost all aspects of their lives since the 80s. Japanese cars, food, entertainment, technology, and fashion have been a part of western culture for almost the entirety of the Millennial and Gen Z paradigm and so it doesn’t seem like a shock that they would so closely hold City Pop as a fond memory that feels forgotten in their own timeline. Japanese Pop Culture consumption in the west has gradually evolved throughout the decades and has always maintained a special place for its spirited and animated takes on things consumers in the west have always loved.

City Pop then is a natural progression for those who maybe once loved Pokemon as a child, or Dragon Ball Z & Sailor Moon even further back. The music reminds them of the association Japanese culture has had with them throughout the years, and this naturally triggers feelings of nostalgia. To denounce enjoying City Pop purely for nostalgic reasons is wholly misguided and missing the point in why the music has become such a force in the cultural matrix of the west.

A reason why this genre resonates so much with younger generations is that City Pop is not trying to sell them anything or get their attention in any way that seems artificial. The draw to it has been an organic evolution that rarely happens in the 20th century. When I was first learning about it in 2015 there were hardly any resources available to learn more except for blogs like Kayo Kyoku Plus, but just within a few years, it created an online fascination so powerful it ballooned to heights no one could have predicted. There is no underlying motive because it’s music that has only recently been revived and made available again. There’s a sincere quality to it in that the artists who made city pop are mostly in their 50s and 60s now and weren’t expecting this popularity to ever even happen.

It’s definitely a surprise for everyone to a point that it seems very much like a feel-good story of the world coming together in a tiny way to celebrate a sub-genre of music that was practically lost to time. This return to what the past meant in our lives and the lives of people far removed from our own is a moment in history that transcends ordinary expectations of what technology can do and how much it can affect relationships between countries and age groups. The genre’s reemergence has become the inciting incident to actually facilitate a co-appreciation of both western and eastern histories in a positive light. A new global nostalgia is being created.

There has been a lot of talk around City Pop recently, and while many still revel in the nostalgic quality of the music, others are criticizing the trend as “Orientalism” or “Asian Fetishism” which are especially condescending terms used to denigrate anyone who seems to enjoy Asian culture in a casual way without expressing some intense analytical understanding of why they enjoy it. This gate-keeping mentality stems from the developing interest in city pop by K-pop stans who often safeguard their preference in music with militant ferocity.

This perspective being perpetuated by critics online wants to make it so that enjoying city pop at a base level is somehow wrong or lacking in sensitivity for viewing the music as anything other than just audio technical machinations created by the Japanese. I disagree that anyone needs a degree in Japanese studies to consider the music good, bad, or even just nostalgic if they so choose.

The fact that even casual listeners are contributing to the sensationalism around the music is not only good for Japan but also good for culture at large regardless of the contentious gaze of online gate-keepers. There’s a certain pretentiousness that always circles genres of music like a vulture and it was inevitable that such elitism would start to form around city pop.

Taeko Ohnuki

The west’s obsession with Japanese culture is not new. A Global Times article reads: “It doesn't matter whether pop Japanese culture in the US is entirely Japanese or not. The thing that matters is that American people like it, which helps Japanese culture take root in American society.” This statement shows that Americans’ willingness to accept Japanese cultural nuances is not rooted in some prejudiced “Orientalist” kind of exotic fetish, but a sensibility that has been long ingrained in the west’s collective psyche as the two sides have become close allies.

“This mingling of Japanese and American culture has been going on for decades.” reads a 2015 article from UK publication Spectator, and those words prove true even today as the cultural relationship of Japan continues to evolve with the west as children and young adults who were once enamored with the culture mature in both taste and preference while becoming contagious to those who formally held no interest in Japan.

Orientalism may have been an issue in the past when Japanese culture was still a mystery to the west, but these days it’s seamless to admire or appreciate Japanese culture even in passing due to how ubiquitous it has become in countries like the US, UK, and Canada. There are of course people that tend to be racist towards Asians abroad and that is very much a real issue that should be taken seriously, but it’s absurd for anyone to think listening to Japanese music for a bit of escapism is wrong. This gravitation towards Japanese culture is long overdue as Japan had already assimilated western culture for over half a century before the proliferation of Japanese culture in the west.

Critics would have you think that a non-Japanese person cannot assign nostalgic attributes to Japanese music without fully exploring the music’s cultural heritage. This subjective and very personal behavior is framed as a faux-pa where if you maybe don’t know Japanese history and simply want to become a fan of anything that country produces you must practice some hyper-introspective meditation on why you enjoy such things to fully justify it.

As someone who has been DJing and collecting Japanese City Pop vinyl records for years, I have come to understand that people simply enjoy good music regardless of origin or age. The fact that the music is Japanese is often an after-thought to the experience which is wholly immersive for the listener. Would it change anything if the music were Thai or Chinese? Possibly, but mostly because phonetically Japanese resonates within the English lexicon and when sung in a western tone and style can bypass the Wernicke's area, located in the cerebral cortex, that processes the understanding of language.

Considering why it’s become so easy for listeners to engage with a foreign language-based music genre you can take into account that there are no difficult to pronounce sounds in Japanese and it contains fewer vowels and consonants than English, which makes it more palatable to enjoy for unassuming listeners regardless of proficiency in the language. That coupled with the Japanese capacity for understanding music theory, western production techniques, and the whimsy thematic nature of genres like yacht rock, jazz fusion, and soft pop makes it the perfect auxiliary language for imprinting false memories of times that never happened. Where there is no inherent meaning the mind will create it.

There is a duality in the music; complex but simple, sometimes subtle, layered with metaphor and double-entendre that escapes those without an understanding of the language’s nuances. Themes often reflect on the easy going lifestyles that were afforded to the burgeoning cosmopolitan socialite class in Tokyo and other major cities at the time. This mindset was explored further in a 1981 slice of life expose written by Yasuo Tanaka titled Somehow, Crystal. The synopsis reads “A journey into the carefree, today-centric generation of Japan's economic boom years, as they enjoy the cosmopolitan lifestyle of Tokyo while exploring new dimensions in Japanese society and self-image.” Indeed, the book has plenty of commentary on affluent young Japanese metropolitan lifestyles that were almost nihilistic in their procurement of “crystal” living.

The book explains how uninterested many Japanese were in actually understanding or looking within themselves to fully enjoy life. On the contrary, they saw life as purely in-the-moment and things were often taken at face value; even the western music that was often mentioned in the book was described in a way as mostly being for purely aesthetic values of self-worth. You did not need to justify why you enjoyed something, or why it made you feel a certain way. Part of being human is acknowledging the ephemeral nature of existence, and nothing is more beneficial to the spirit than experiencing something without being told how to experience it. Ultimately, you decide for yourself what you want from your experiences.

Sugar Babe

The real reason why many people, including myself, constantly covet the “nostalgic” quality of city pop is not a mystery. The production techniques used to create the lush sounds were being imported from the west and enhanced with Japanese artistry and talent creating a soft parallel to major musical breakthroughs happening in cities like Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago. Much of the music that was available to the west in the mid-70s to early 80s were undoubtedly fueling the inspiration for a wave of Japanese musicians that borrowed heavily from artists like Steely Dan, Michael Jackson, and George Benson who’s flavors and flair were fused to create what is being called the city pop sound.

The analog tape used to record these songs still has that warm fuzz that calls back to the pre-digital recording days when music sounded like it was made by an actual person and not an algorithm. Many years of progress in audio-engineering equipment created the perfect, artifact-free recording that has consequently stirred a longing for what makes something unique to begin with; imperfection. It does not take years of study to understand why this music is looked at as being timeless.

The need for vulnerability and true feeling in contemporary music has added momentum to city pop’s rise as it contradicts the music of today by not sounding artificial, insincere, or contractually obligated to perform for your pleasure. The music reminds us that there was another past, another way of life and that is a catharsis for a generation that has experienced trauma after trauma in their short lifespans. So if anyone wants to take comfort in city pop’s nostalgia then they should be able to without feeling guilty. - Van

AUTHOR

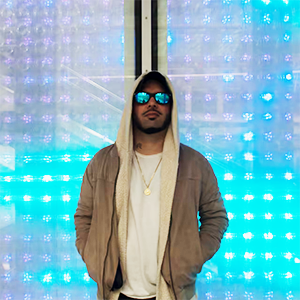

Van Paugam is an Internationally-Acclaimed DJ and leading figure specializing in 70s and 80s Japanese Music, dubbed City Pop. He has organized and hosted over 100 events dedicated to the style, and actively promotes Japanese culture while on the board of the Japanese Arts Foundation of Chicago. He has been featured on CNN, NHK, and many other publications for his dedication to City Pop. Van is credited with being the first person to begin popularizing City Pop online through his mixes on YouTube in 2016, and subsequently through live events. Learn More…

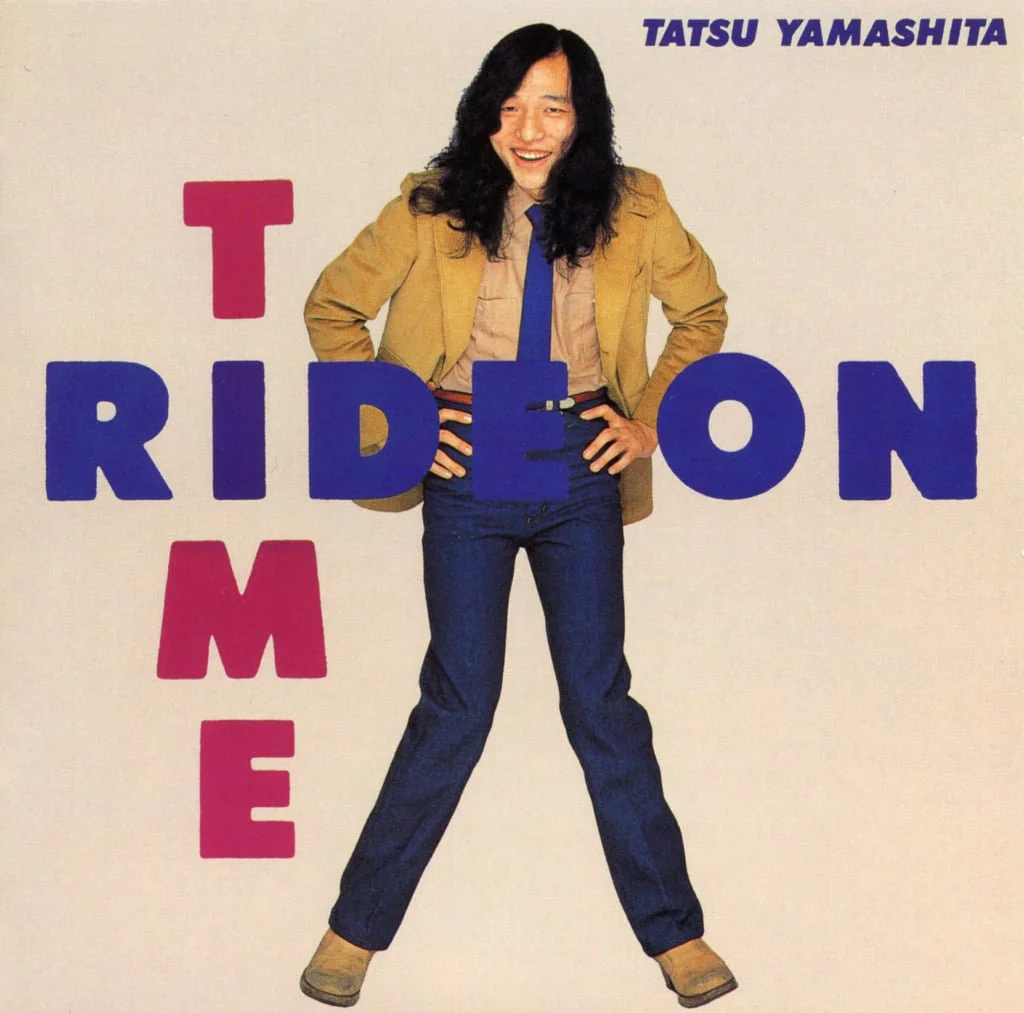

A closer look at the recent copyright takedowns issued by Tatsuro Yamashita, and others, and the war on the online content creators that helped bring City Pop into the global spotlight 40 years after its heyday.