Shikago: The Meiji-Era’s Lost Spelling of ‘Chicago’

市俄古

When I applied for the 2025 Individual Artist Project Grant from the City of Chicago, I didn’t know what to expect. There are so many artists here, so many incredible voices and visions, all trying to carve out a small piece of recognition. But I kept returning to this strange, beautiful idea that had haunted me for a while. A name. A spelling. Three kanji that used to represent this very city.

市俄古. Shikago.

It looks like something pulled from a crumbling Meiji-era document or maybe from a weathered storefront sign in a forgotten part of town. But it’s not made up. It’s real. This was how some early Japanese sources used to spell Chicago, long before katakana standardization. It’s a version of the city that doesn’t show up on maps anymore. Most people have never seen it. And I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

In the late 1800s, Japan was reinventing its language. New machines, new music, new ideas all rushing in from the West. Demanded new words. But instead of simply borrowing terms wholesale, Japanese scholars and printers tried something more poetic. They rewrote the foreign world in kanji under what is called ‘Ateji.’

Ateji is the practice of assigning Chinese characters to foreign words based on sound, not meaning. “America” became 亜米利加. “Coffee” became 珈琲. And Chicago? It became 市俄古.

This archaic spelling of the word “Chicago” survives in few places today. It appears fleetingly in Meiji- and Taisho-era encyclopedias, in early newspapers, and in trade route maps that now gather dust in rare book archives. Most Japanese speakers today have never seen it. Fewer still could read it aloud.

The Meiji Restoration (1868–1912) was a cultural revolution as much as a political one. Japan was opening itself to the world after centuries of relative isolation, and with that came a crisis of translation.

But to me, it reads like a ghost story. A half-erased connection between the city I live in and the culture I’ve spent years honoring through sound.

A Name Buried in the Past

In Japanese, foreign words are often written using katakana. It’s the script used for borrowed terms, like チーズ (cheese) or コンピュータ (computer). Chicago is now シカゴ. Clean. Functional. Phonetic. But before katakana took over, the Japanese language sometimes leaned on ateji, the use of kanji characters to approximate foreign sounds rather than meanings. This produced spellings that were part phonetic puzzle, part poetic artifact.

That’s where 市俄古 comes in.

The first character, 市 (shi), means "city." The second, 俄 (ka), can refer to suddenness, depending on the context. The third, 古 (go), means "old." Together, they don’t form a literal translation of Chicago, but they capture a sound. They embody a mood. There’s a strangeness to them, like a dream of a place you’ve never visited.

Why I’m Bringing It Back

When something is forgotten long enough, it starts to take on power. You begin to wonder why it was left behind. Was it too complicated? Too poetic? Not modern enough?

For me, 市俄古 feels like a doorway into a different way of seeing Chicago, into the relationship between Japanese and American cultural memory. Chicago has played a significant role in the formation of modern music, and Japan has responded in kind, creating genres like City Pop that wouldn’t exist without the grooves of Chicago soul, jazz, funk, and house music.

But no one really talks about that connection. Not in a way that honors both histories.

This is where the kanji come in. I will to turn them into a neon sign, glowing in the window of The Whistler, a bar I’ve had quite a history with.

I think a lot about how we remember things. Records are one way. Zines. Flyers. Crates of old vinyl. Neon signs. All of these objects carry stories, even when we stop noticing them.

The sign will be designed with careful reference to traditional Japanese aesthetics. Not flashy. Not ironic. It will look like it could have existed in 1885 or 1985 or 2025. It will borrow from the visual vocabulary of Edo signage, filtered through the nightlife energy of Shibuya in the early 80s. The glow will be muted but deliberate. This isn’t nostalgia for its own sake. It’s time travel. It’s translation.

I want people to see the sign and wonder what it means. I want them to ask questions. To take a photo. To look it up. To fall into a Wikipedia hole. To tell a friend. That curiosity is the beginning of understanding. And the beginning of understanding is the seed of cultural connection.

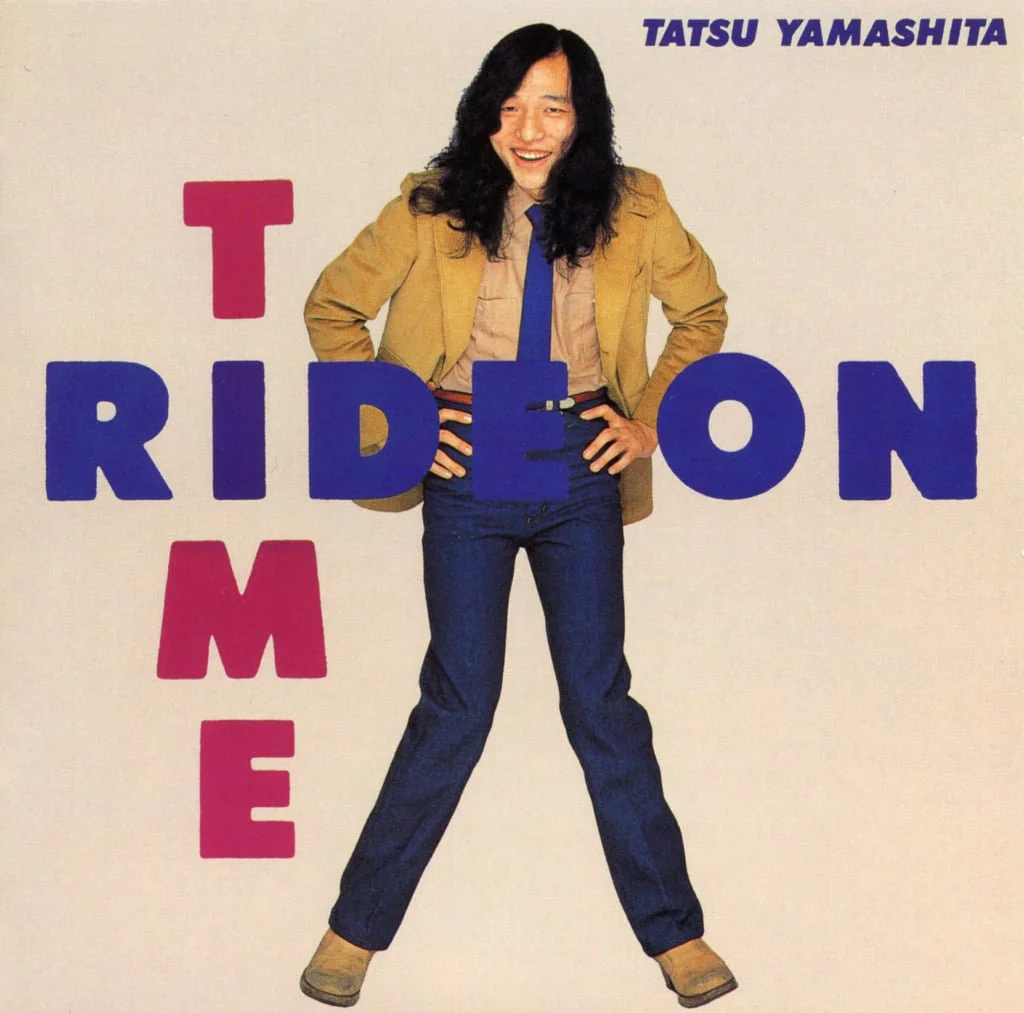

It’s easy to think of City Pop as a purely Japanese export. But like most music, it exists because of a feedback loop. Japanese musicians in the late 1970s and '80s were heavily influenced by American soul, funk, jazz fusion, and Chicago house. Artists like Tatsuro Yamashita and Taeko Ohnuki weren’t copying, they were reflecting. Translating.

That feedback loop continues now in reverse. DJs in the U.S. are rediscovering Japanese records and bringing them into new spaces. It’s not revivalism. It’s recognition.

What the Grant Makes Possible

Thanks to the support from the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE), I’m able to bring this idea into the real world. The grant will cover the design and production of the neon sign, as well as the initial programming tied to its unveiling.

That unveiling will include something I’ve dreamed about for a while which I will reveal at a later time.

All of this will take place under the new project identity I’m building: the Shikago Foundation. It’s a name that suggests a place that’s both real and imagined, historical and speculative. The foundation will serve as a platform for future events, writings, and creative work that explores the forgotten and overlooked connections between Japanese and Chicago culture.

Chicago is a set of overlapping histories, many of which haven’t yet been properly told. This project is about telling one of them not through a textbook or a panel or a lecture, but through a sign. A shape. A light in the window that says, this city has layers you’ve never seen.

And sometimes, to see them, all you have to do is learn how to read again.

市俄古.

Shikago.

A name you didn’t know you had forgotten.